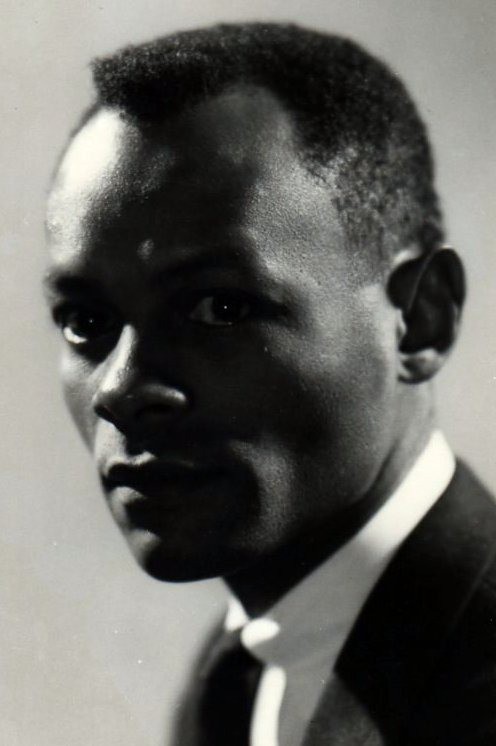

Hughie Lee-Smith (1915–99)

Hughie Lee-Smith portrait, date unknown. Courtesy of Stephanie Patterson, Galerie Hughie Lee-Smith, Santa Barbara, CA.

Hughie Lee-Smith started art classes in 1925 at the age of 10 while living in Cleveland, Ohio, with his mother Alice.[1]She recognized his talent at a young age and became determined to give him the opportunity to pursue it. [2]

During the Great Depression, there were few scholarships for students, but Lee-Smith received two. In 1934, he won his first scholarship, which allowed him to study at the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts. The following year, he received the Gilpin Players scholarship to study at the Cleveland School of Art (later renamed the Cleveland Institute of Art). He was the second Black student to be admitted to the school, the first being Charles Salleé, who was admitted in 1934. Lee-Smith graduated from that institution in 1938 with honors. He was one of three Black students.

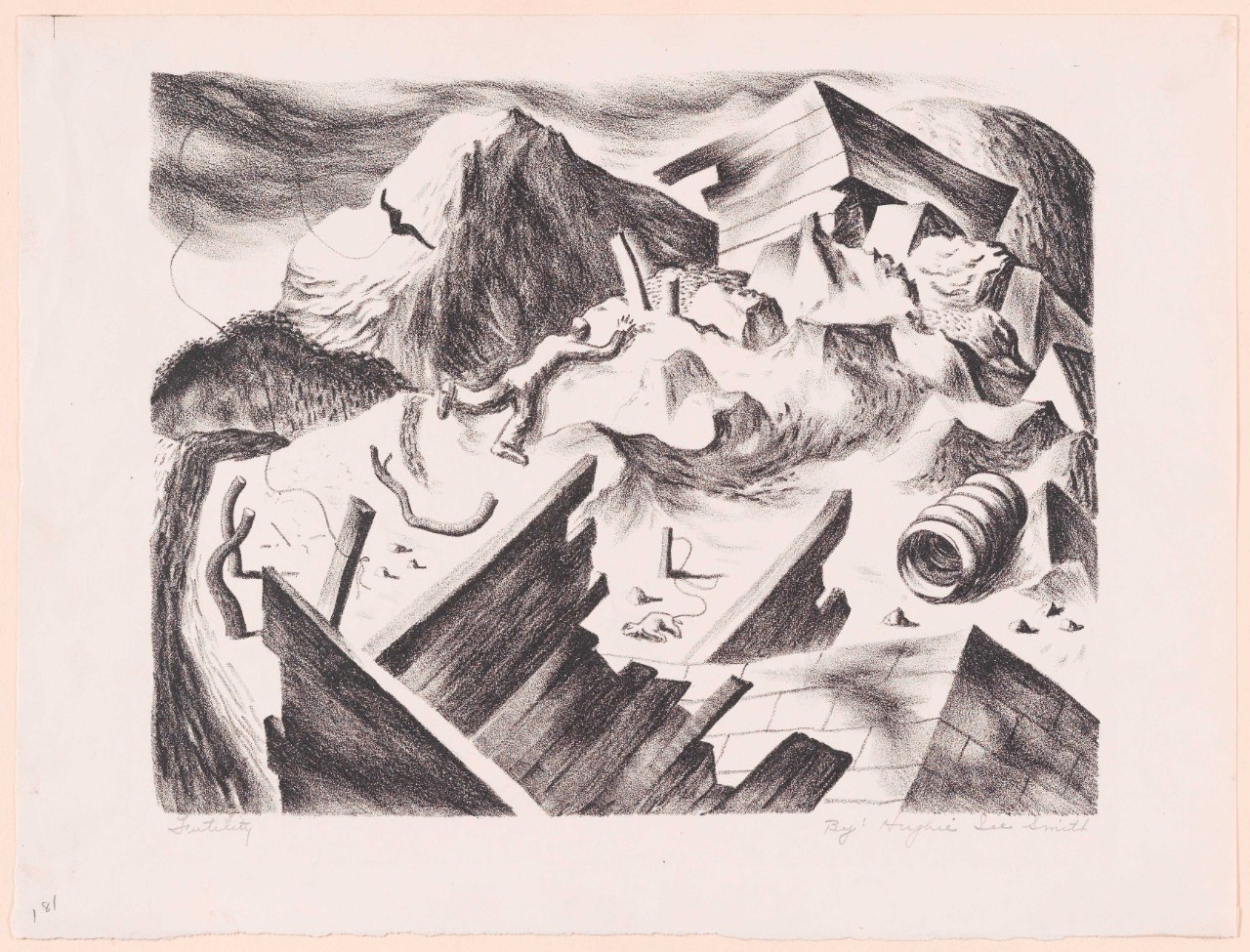

In the aftermath of the economic crash in 1929, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Works Progress Administration (WPA)—later renamed the Work Projects Administration—to curb the effects of mass unemployment in the midst of the depression. One of the work relief programs created under this administration, the Federal Art Project (FAP), focused on funding the visual arts. After graduation, Lee-Smith was employed as a printmaker under this program, creating lithographs to be displayed in government buildings, schools, and hospitals around the city of Cleveland. In these works, he rendered the figures in his artwork using a social realist style, which he continued to utilize throughout much of his career. Many of these works were later donated or sold off when the WPA gradually shut down as the country transitioned their workforce in defense of the nation in the early years of World War II.

Hughie Lee-Smith, Futility, lithograph, c. 1935–43, 8.5 x 11 in, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY.

After his work for the WPA, Lee-Smith took a job in Orangeburg, South Carolina, as an art teacher at the historically Black Claflin College. While living in South Carolina, he met and married his first wife, Mabel.[3]Faced with the responsibility of earning a steady paycheck, the couple moved to Detroit, where Lee-Smith started working at the Ford automobile factory.

Prior to the U.S. entry into World War II, the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 required all American men between the ages of 21 and 35 to register for a national lottery for military service. As required by law, Lee-Smith was among those who registered for the draft. While working at the Ford factory, he also continued to circulate his artwork. He had an exhibition in 1942 at the Karamu House in Cleveland. This exhibition included Landscape No. 1, which he had created during his time with the WPA.

Hughie Lee-Smith, Landscape No. 1, linocut, c. 1939, 9 7/16 x 10 3/4 in, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland OH.

In 1943, Lee-Smith won first prize in an exhibition of Black artists at Clark Atlanta University.[4] That same year, he was drafted into the U.S. Navy. He reported for active duty on 20 January 1944. He was assigned to Naval Station Great Lakes, near Chicago. He spent the next 19 months of the war at this base, serving as an official painter responsible for “morale paintings” at Camp Robert Smalls. He also worked with two other Black seamen, Edsel Cramer and Isaiah Williams. Both Cramer and Williams also had received an art education before the war. Cramer had attended the Art Institute of Chicago, and Williams had studied at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Arts.[5]

Hughie Lee-Smith (right), Edsel Cramer (left), and Isaiah Williams (far left) in front of a mural at Camp Robert Smalls, c. 1944. (Great Lakes Bulletin, 21 April 1944)

Lee-Smith’s first solo exhibition was held at Chicago’s South Side Community Art Center in 1945. Among the paintings displayed, the exhibition featured works inspired by his time in the Navy, including one titled Machinist Mate, World War I. [6] He received his honorable discharge on 23 August 1945.[7] Following the war, the collection of murals painted for the recreation building at Camp Robert Smalls were donated to the South Side gallery.[8]

Lee-Smith went back to school using funds granted by the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944 (commonly known as the G.I. Bill), attending Wayne State University in Detroit. He earned his bachelor’s degree in art education in 1953. That same year, he received an award for painting from the Detroit Institute of Arts. Over the course of the next decade, his artwork reflected themes of isolation and desolation in the urban environment. He may have also been reflecting on his own feelings about being Black in America during this time.

Lee-Smith never forgot his service in the U.S. Navy. He returned to the theme of Blacks serving in the military during his tenure as an artist-in-residence at Howard University from 1969 to 1971.

In 1971, he began working on commission for the Navy as a combat artist. His first commission was a portrait of Rear Admiral Samuel L. Gravely followed by another painting featuring Black sailors at the prow of George Washington’s boat crossing the Delaware. Both of these works were incorporated into the official Navy combat art collection held at the Washington Navy Yard.

Hughie Lee-Smith, Rear Admiral Samuel L. Gravely, oil on canvas, c. 1972, 48 x 38 in, Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), 88-162-TL.

Hughie Lee-Smith, Navy Black History, oil on canvas, c. 1972, 51 x 39 in, NHHC, 88-162-TM.

Although he did not work as a full-time artist for the Navy, Lee-Smith continued to accept commissions from the Navy while he exhibited his own work at commerical galleries and museums. In 1977, the Navy’s first Black officers organized their first reunion, at which they adopted the name “The Golden Thirteen.” Lee-Smith attended the reunion in his role as a combat artist, completing a commemorative artwork for this event to add to the Navy’s collections.

Hughie Lee-Smith, Reunion, oil on canvas, c. 1977, 28 x 43 in, Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), 88-162-TN).

Throughout his career, Lee-Smith created art that reflected on his own experiences and beliefs about the role of art in promoting social change. He used his experience serving in the Navy during World War II and his belief in equal recognition for all Americans to promote the change that he wished to see in America.

Hughie Lee-Smith passed away in 1999 at the age of 83.[9]

—Kati A. Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division, April 2024

***

NHHC Resources:

African Americans in the Navy in the 1970’s and beyond

Further reading:

Depillars, Murry N., “Chicago’s African American Visual Arts Renaissance.” In The Black Chicago Renaissance, ed. Darlene Clark Hine, and John McCluskey Jr. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2012.

King-Hammond, Leslie, and Hughie Lee-Smith. Hughie Lee-Smith. Petaluma, CA: Pomegranate Communications, 2010.

Wilson, Alona C. “The Formation of an African American Artist, Hughie Lee-Smith, from 1925 to 1968.” PhD dissertation, Boston University, 2016.

***

Notes

[1] Hughie Lee-Smith was born with the last name, Smith, but he later changed it to combine his middle name (Lee) with his last name (Smith).

[2] “Hughie Lee-Smith ’38,” Link, Winter 1981, p. 12–13.

[3] Hughie Lee-Smith, Mabel [Portrait of the Artist's Wife], oil on canvas, c. 1940, 38 x 34 in, National Museum of African American History and Culture, (2016.172), Gift of Stephanie Anne Patterson.

[4] Lee-Smith, Unusual Landscape, oil on canvas, c. 1943, Clark Atlanta University, Atlanta, GA.

[5] Michigan Chronicle, 13 May 1944; Pittsburgh Courier, 13 May 1944.

[6] Chicago Tribune, 20 February 1945.

[7] Notice of Separation from the U.S. Naval Service, Hughie Lee-Smith Papers, circa 1890–2008, bulk 1931–1999, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

[8] Hughie Lee-Smith, "Oral history interview with Hughie Lee-Smith, 1968," interview by Carroll Greene, Archives of American Art; Pittsburgh Courier, 13 May 1944. The current whereabouts of this series of murals is unknown. The painting titled Special Training Unit held by the Naval History and Heritage Command is most likely one of the early studies completed for this series, but the dimensions of this work are not large enough to be one of the murals. Images of the murals were printed in newspapers in 1944, but otherwise the murals are lost.

[9] New York Times, 1 March 1999.

Published: Mon Apr 15 11:57:25 EDT 2024